A photo posted on the Mount Washington Observatory’s Facebook page this month shows a particularly hazy sunrise resulting from smoke that drifted east from West Coast wildfires.

In 2018, California’s wildfire season brought higher death counts, greater financial destruction, and longer burning seasons—a record that has now been surpassed by this year’s devastating West Coast wildfires. The state’s unharmed residents were left to a wave of smoke-polluted air that shut down schools, evacuated survivor camps, and prompted local officials to hand out respirator masks just so citizens could breathe. The impact of this smoke pollution lingered beyond the duration of the flames, spreading outside the boundaries of the wild fire itself. After California’s 2017 and 2018 wildfire seasons, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists observed huge swaths of the hazardous smoke traveling across the country, a phenomenon that continues to occur now.

The Northeast impact is typically minor compared to that in the West, but such events provide an alarming example of how widespread wildfire impacts can be in certain conditions. Amid the fires raging this September across massive swaths of California and Washington, satellites have detected smoke high above East Coast cities and as far east as Europe. A photo posted on the Mount Washington Observatory Facebook page showed the resulting haze seen from the peak’s summit, and Jeff Underhill, chief scientist of atmospheric science & analysis at New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services, notes moments when conditions allowed for a heavier impact, citing Canada’s Fort McMurray wildfire in 2016. The fire burned for four months and destroyed 1,500,000 acres of land in northwestern Canada, resulting in a cloud of hazardous particulate matter that drifted all the way to the Midwest and Northeast United States. The smoke came in tandem with a dangerous ozone bloom, an occurrence Underhill says is common during major wildfires.

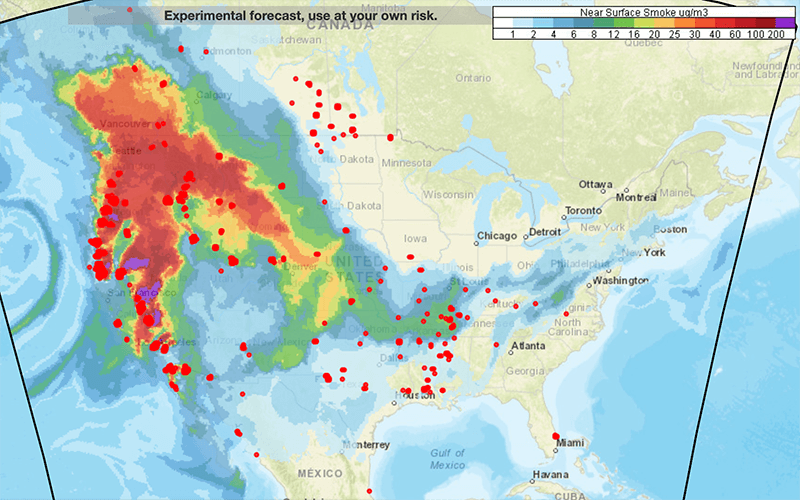

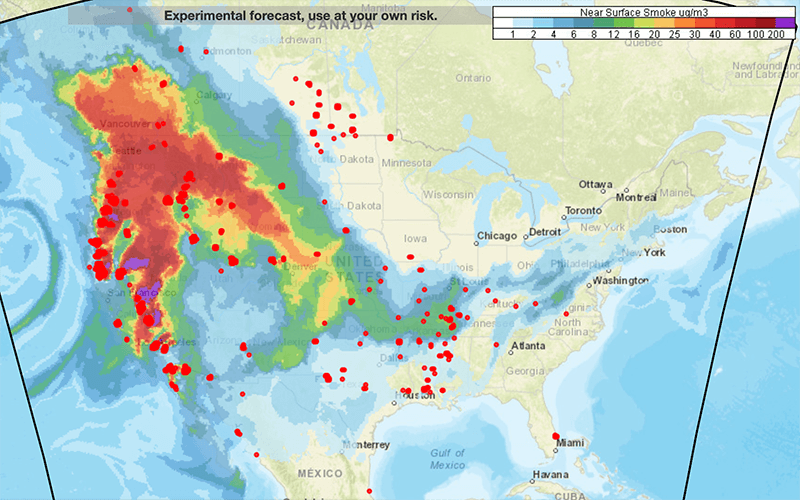

Based on satellite observations of fire location and intensity, NOAA’s HRRR-Smoke forecast predicts the movement of smoke in three dimensions across the country over 48 hours, simulating how the weather will impact smoke movement and how smoke will affect visibility, temperature, and wind. This smoke forecast is from September 17.

The Environmental Protection Agency monitors these occurrences, tracking both fine particulate pollution and ozone presence across the country. They use an air quality index (AQI) to warn the public about associated dangers. The index spans from green “good” to the extreme “hazardous” that Pacific Coast residents are seeing this year. Right in the middle of their index lays the orange “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” indicating a danger warning for vulnerable populations—children, elderly, anyone with respiratory diseases, and, perhaps most surprisingly, hikers.

“People outdoor exercising are in this sensitive group,” says AMC’s staff scientist Georgia Murray. “Because we’re recreating and breathing deeply, hikers are exposed to overall more pollutant load.”

In mid-September, the University of Maryland–Baltimore County’s Smog Blog reported that wildfire smoke detected by Lidar is “confined to heights at 3 to 10 kilometers and not impacting the surface air quality measurements.” That’s why Underhill says smoke drift generally affects those hiking at higher elevations. An AMC study on Mount Washington hikers confirmed that certain air pollutants decreased lung capacity even in healthy adult hikers.

At Camp Dodge’s air quality monitoring station, Murray has noticed the traces of atmospheric carbon following distant wildfires. Fresh smoke can affect the ozone levels, she says, but most often we see the impacts in the haze levels and chemistry. For Murray, the smoke drifting from the West is both a health concern and a warning. “The western forest fires are severe enough,” she says. “They’re in public lands and they’re in communities that are right up against public lands. Even though it may not be affecting us as directly, I think it’s a wake-up call to us all that climate change is happening now.”