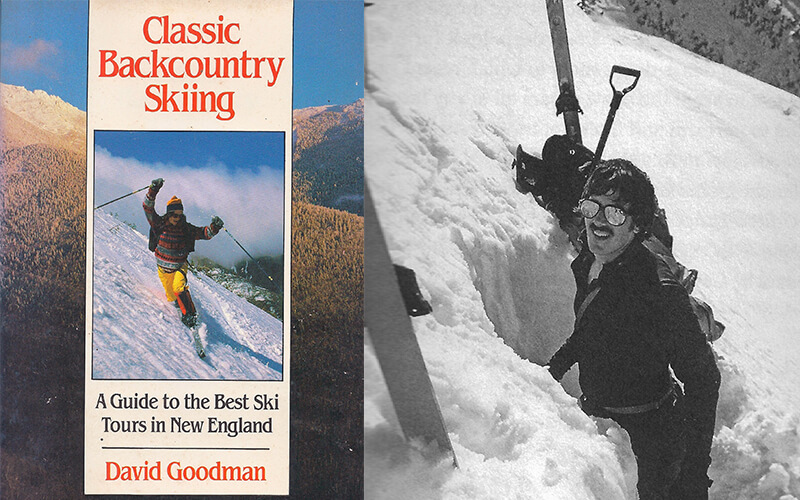

David Goodman’s Classic Backcountry Skiing—first published in 1988–89—became a trusted backcountry skiing guidebook for many Northeast adventurers.

In 1987, I received a phone call from a books editor at the Appalachian Mountain Club. Would I be interested in writing a backcountry skiing guidebook for New England?

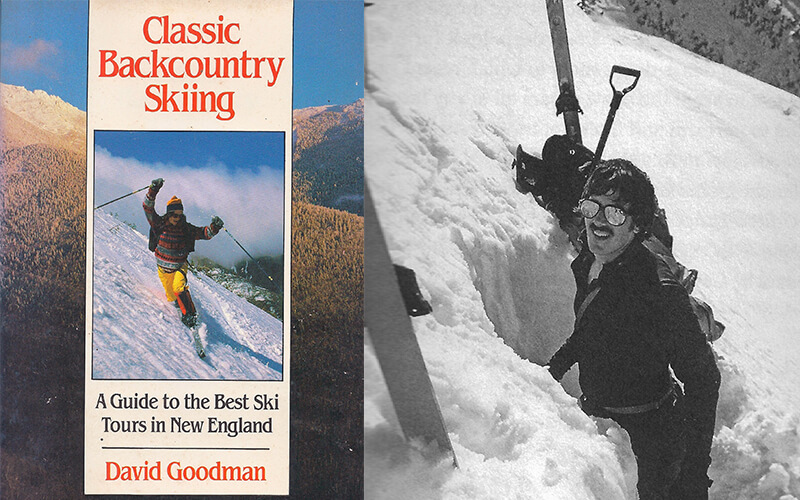

I was a 27-year-old budding journalist, ski bum, political activist, and climber; I’d never written a book. The invitation seemed incredible: Somebody wanted to pay me (well, barely) to sniff out and write about the best powder skiing in New England.

Perhaps foolishly, the editors left it to my discretion how to approach the project. I was later told that some at AMC considered it “radical” to publish a ski book. AMC was a hiking organization, argued the skeptics at the time, and had no business promoting skiing. This sentiment was amusing to me: as a ski history buff, I knew that AMC was one of the foremost promoters of skiing in the 1930s, organizing clinics, competitions, and “snow trains” that transported enthusiasts from Boston and New York City to ski in places such as Mounts Washington, Cardigan, and Greylock.

I got to work researching the new guidebook. I pored through old maps to find forgotten trails and spent a winter living out of my 1974 Dodge Dart, skiing my brains out all over New England with friends. I was working as a mountaineering instructor for the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School based in Maine, which provided me with a large pool of marginally employed comrades who were always up for insane adventures. I provided plenty of those. Like the attempt to circumnavigate Mount Mansfield in Vermont when my partners and I got lost and ended up knocking on the door of the first house that we encountered: a substance abuse recovery center that was hosting a dry New Year’s Eve celebration. They generously offered our cold crew slices of warm pie.

I combined my passion for history (my major in college) with my love for high and wild places by skiing in the highest mountains of New England and researching the ski history. Outside of Tuckerman Ravine, the high peaks had been largely abandoned by skiers. But I had heard stories about how skiers had been crisscrossing the great ranges of New England since the 1920s. I wanted to learn where these skiers had gone and hear their tales. Perhaps, I speculated, the seeds they planted could blossom again. I sought out and interviewed many of the people who designed, cut, and skied trails in the 1930s and 1940s. As they described this rich era of ski exploration, a forgotten subculture came back to life. I went hunting for buried treasure—and found it on the Teardrop Trail on Mount Mansfield, Thunderbolt Trail on Mount Greylock, and Tucker Brook Trail on Cannon Mountain, to name a few. I felt a thrill every time I found and skied one of the historic trails, as if I were reconnecting part of New England’s past with its present.

Skiers have been navigating Dodge’s Drop on Mount Washington for nearly a century.

Thus was born Classic Backcountry Skiing, which AMC Books published the winter of 1988–89. I figured 100 backcountry skiers would buy it, and I would know 95 of them. To my amazement, the book had a wide audience, selling 5,000 copies in the first two years. I’d often see dog-eared loose-leaf copies—the binding was defective and the pages fell out—on dashboards of cars at trailheads all around the region. The book won two national awards, and Backcountry Magazine dubbed it “the Eastern backcountry bible.” Classic Backcountry Skiing came out just as interest in backcountry skiing in the Northeast was blossoming. People were looking for an alternative to the increasingly crowded and commercial downhill ski scene. They found it right in their own back yards.

Venturing into the wilds often involves misadventures, and researching this book over the years has had its share of them. There was the time my partner broke a ski halfway through a 20-mile traverse of the Pemigewasset Wilderness; the snowshoers I encountered in New Hampshire who were clinging to a tree 20 feet off the ground, terrified of a moose calf on the trail (I shooed it away so they could climb down); the easy ski tour in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom that ended with me getting lost and hitchhiking 20 miles back to my car in the dark. But nothing could top the day that I and two partners were threatened with arrest by ski patrollers in Vermont, who accused us of “illegally” skiing “their” mountain after exiting from the Long Trail, which passes through their (largely publicly owned) terrain. Alas, petty tyrants are no match for backcountry skiers; vanishing into the trees turns out to be a fun way to solve the problem.

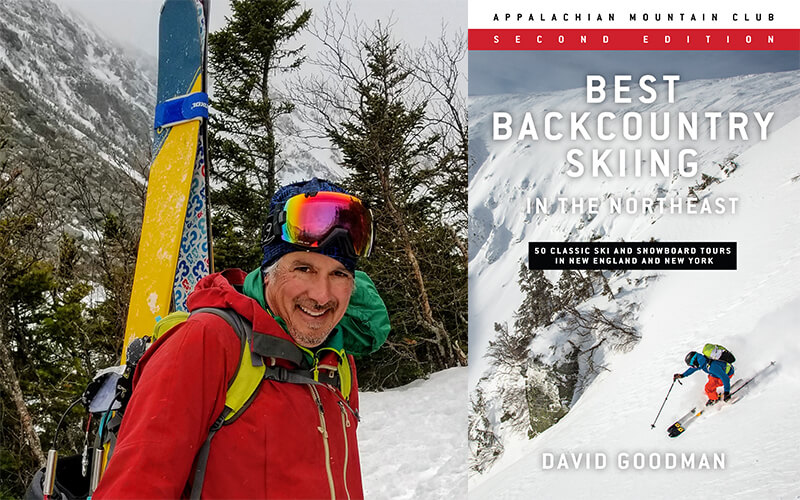

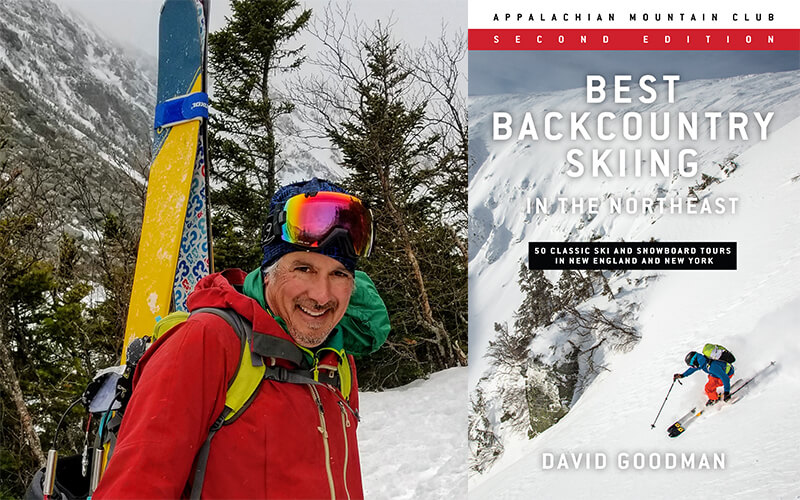

Much to my surprise, writing a skiing guidebook has ended up being a lifelong gig. AMC keeps calling, and I keep updating the guidebook every decade; the fourth iteration—Best Backcountry Skiing in the Northeast: 50 Classic Ski and Snowboard Tours in New England and New York—has just been published.

Now in its fourth iteration, David Goodman’s Best Backcountry Skiing in the Northeast (formerly Classic Backcountry Skiing) is a leading backcountry skiing guidebook.

Backcountry skiing, and the world, has changed dramatically over the life of this book. Innovations in alpine touring, or AT, ski gear has revolutionized the sport, enabling downhill skiers to easily ski the backcountry, provided they learn basic backcountry skills, including avalanche awareness. Backcountry snowboards, aka splitboards, now enable snowboarders to travel deep into the mountains and ride untracked snow.

Backcountry skiers have emerged from their secret stashes to form a vibrant community. Granite Backcountry Alliance in New Hampshire and RASTA in Vermont are vanguards of this community-supported skiing movement, working with stewards of public lands to expand recreation and leading volunteers to cut new ski terrain for an eager public. The COVID-19 pandemic has added to the perfect storm that is motivating skiers to avoid crowded resorts and strike out for wilder places. The boom in interest has been building dramatically: REI reported that sales of backcountry ski equipment has tripled in just the last year.

Then there is the climate crisis. Skiers can no longer take winter for granted. We must use our passion for the outdoors to organize with climate action groups including AMC, Protect Our Winters, and 350.org to save our winter habitat—and our sport.

Since receiving that serendipitous phone call from the AMC more than three decades ago, these beautiful mountains have elated, humbled, and humored me during the countless adventures that I have been lost and found while skiing here. It doesn’t matter where you go, just that you go. May these snowy summits entice you to venture into the rarefied mountain air, embrace you with powder, and feed your soul—as they have done for me.