The White Mountains were a playground for Roger Whidden and his children, who experienced togetherness and the healing power of nature in those hills.

I awaken my children from their car ride-induced slumber as we approach New Hampshire’s “Old Man of the Mountain”—back when you could still spot a face in the Cannon Mountain outcropping—on the highway below. “Now we get to climb up to touch the clouds,” exclaims Jian, my youngest at six years old, from the back seat.

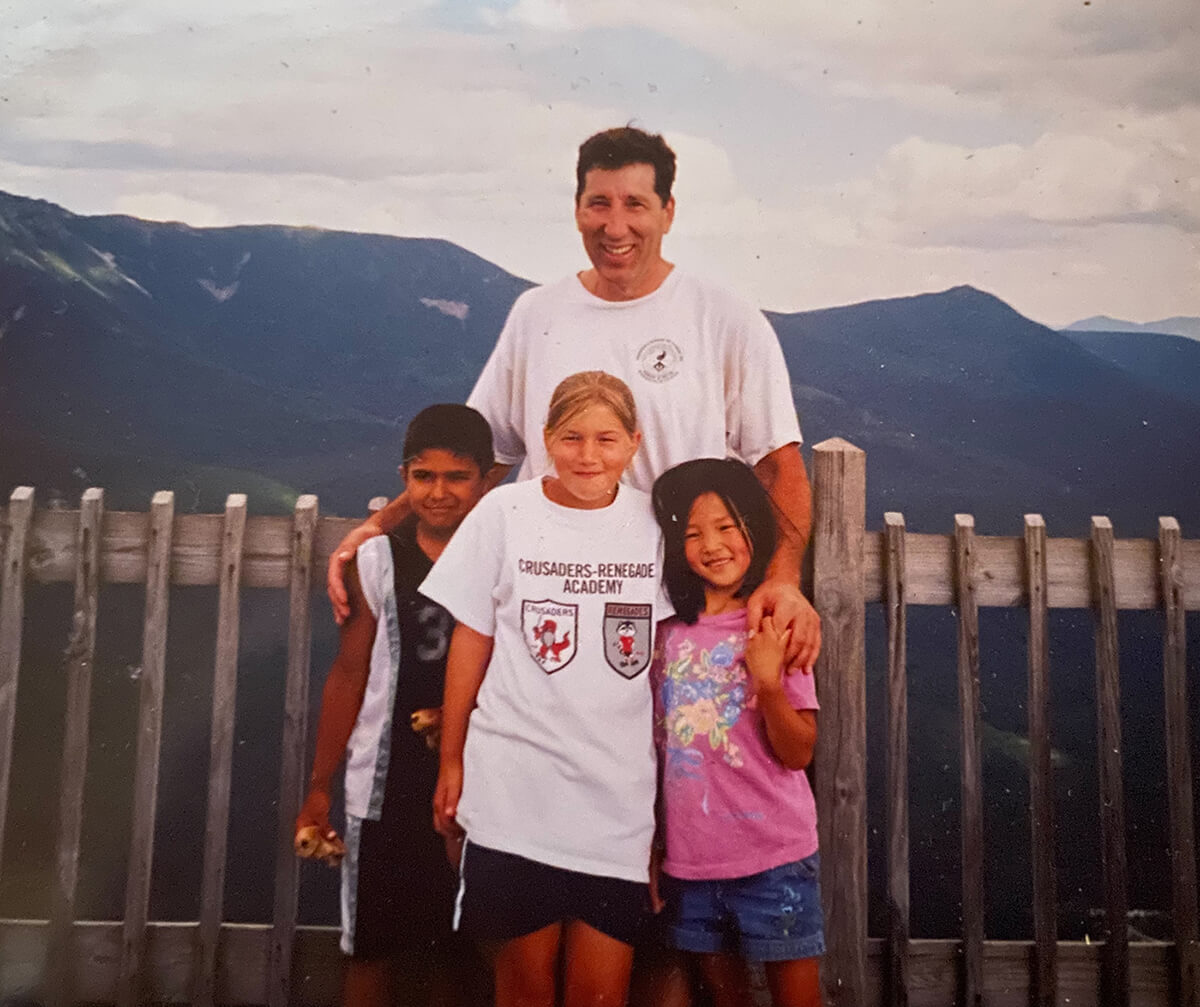

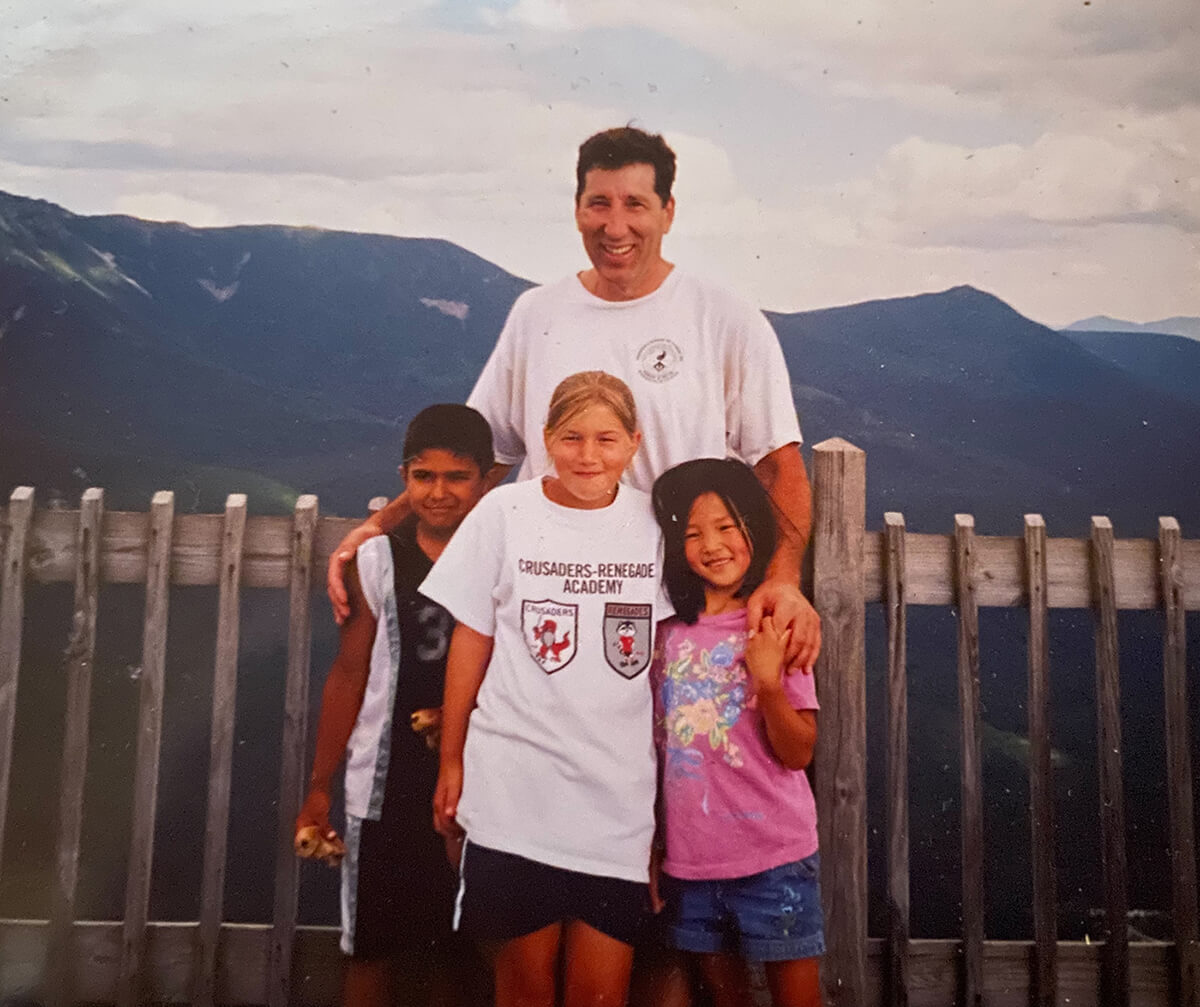

It’s 2001, and we’ve arrived at Cannon’s summit via Ridge Trail—what my son calls “the stairway to heaven” trail—which parallels the aerial ski tramway. Secure on the platform deck that connects to the rim trail, we are met by clear skies and panoramic beauty. A curious group of foreign tourists clicking their cameras approaches us. An interpreter inquires as to how we got here, and my children proudly proclaim that we hiked. We also wonder aloud how they got to the top, as we did not know that the tram operated in the summer. We all laugh as we clumsily negotiate the impromptu nature of our cross-cultural outdoors experience. We gladly pose for their pics, and they make sure that my wee Asian daughter is in the center of the mix.

This kind of encounter has happened more than you might expect, especially with my grown-up children were younger. You see, we are a transracial adoptive family. There’s Jocelyn, a U.S.-born blond and blue-eyed girl; Cory, a brown Bogota, Colombia-born boy; and Jian, a Wuhan-born girl of Chinese descent. “Everyone knows Wuhan now,” declares Jian today as she negotiates the benefits and challenges of her “Asian face” and her biracial son through this complex COVID-19 crisis. Then there’s me, a tall, white martial artist.

Whidden and his three children—Cory, Jocelyn, and Jian—at the summit of Cannon Mountain in 2001.

When Jocelyn was young, I would throw her onto my shoulder and head out the door as a way to harmonize her strong energy. She learned to regulate her emotions through our daily walks to our local beaches. Cory loved all outdoor adventures, and my friends would often ask if I could bring him on our skiing and hiking trips. Cory called us the “old ugly men” (OUM) and jumped at the chance to have an “OUM” meditation-in-motion outing with us. One of my son’s best friends, Sean, has had the same dream each year on Cory’s birthday, also the date of his passing nine years ago. Sean says that Cory tells him that his spirit has a home in our local Blue Hills Reservation—the site of our last hike together here on Earth. Jian gyrated with joy just being their little sister, especially regarding outdoor adventures. These days, Jian is still grounded by walks in local forests and tending to her veggie garden. I tend to be the go-to outdoor guide for her son, Tristan. At four years old, “Mr. T,” as I call him, is interested in animal tracks and scat as well as bird songs.

When the kids were five, seven, and nine years old, extreme weather turned us back at AMC’s Lakes of the Clouds hut on our first attempt at summiting Mount Washington. We’d successfully summit it six years later with the support of several multi-national and multi-racial friends. It was a family bonding experience that helped lead us through the shock of the dissolution of my marriage. The cross-cultural community climb to the summit was such a profound experience for us that our moods elevate at the mere mention of it.

Despite the curious looks we sometimes draw, overt racial tension rarely cropped up for us on the trails. For many, the great outdoors may massage strangers’ thorniness into more flexible and appropriately permeable boundaries. Having a tall, white dad who is a martial arts master may have given us a pass, too.

However, when judgment crystallized and surfaced in the form of a mean stare or harsh words, each child handled the situation uniquely. Jocelyn would dig her heels down for the support and empowerment of Mother Earth. Cory would melt the mean metal mentality with his sunshine smile. And Jian would hug me like Velcro so as to leave no doubt that we are family in heart, mind, and soul—even if we’re not all connected biologically. Generally, perplexed people would move toward ease and then ask curious questions. Occasionally, we would need to distance ourselves from a situation and regroup as a family.

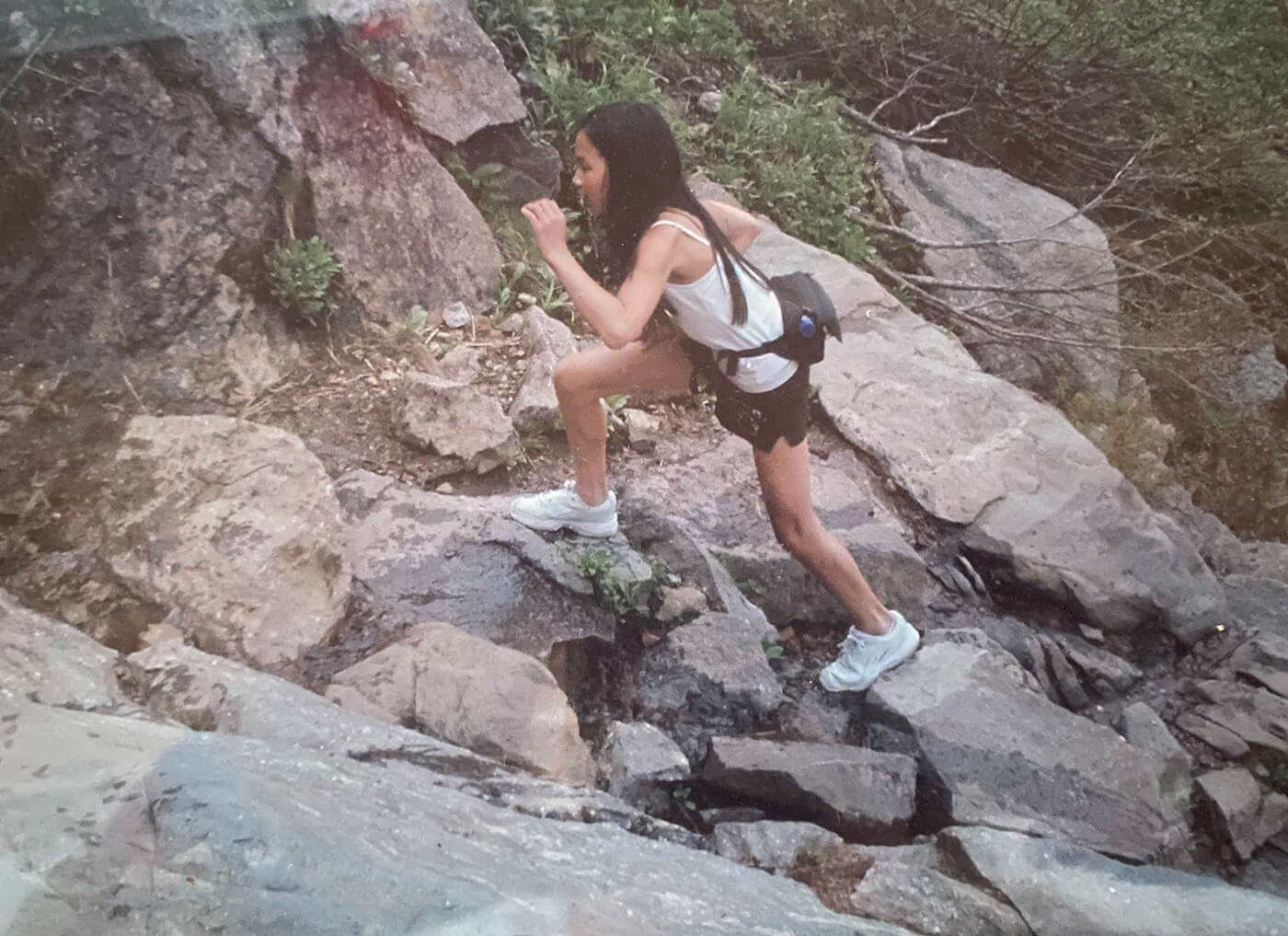

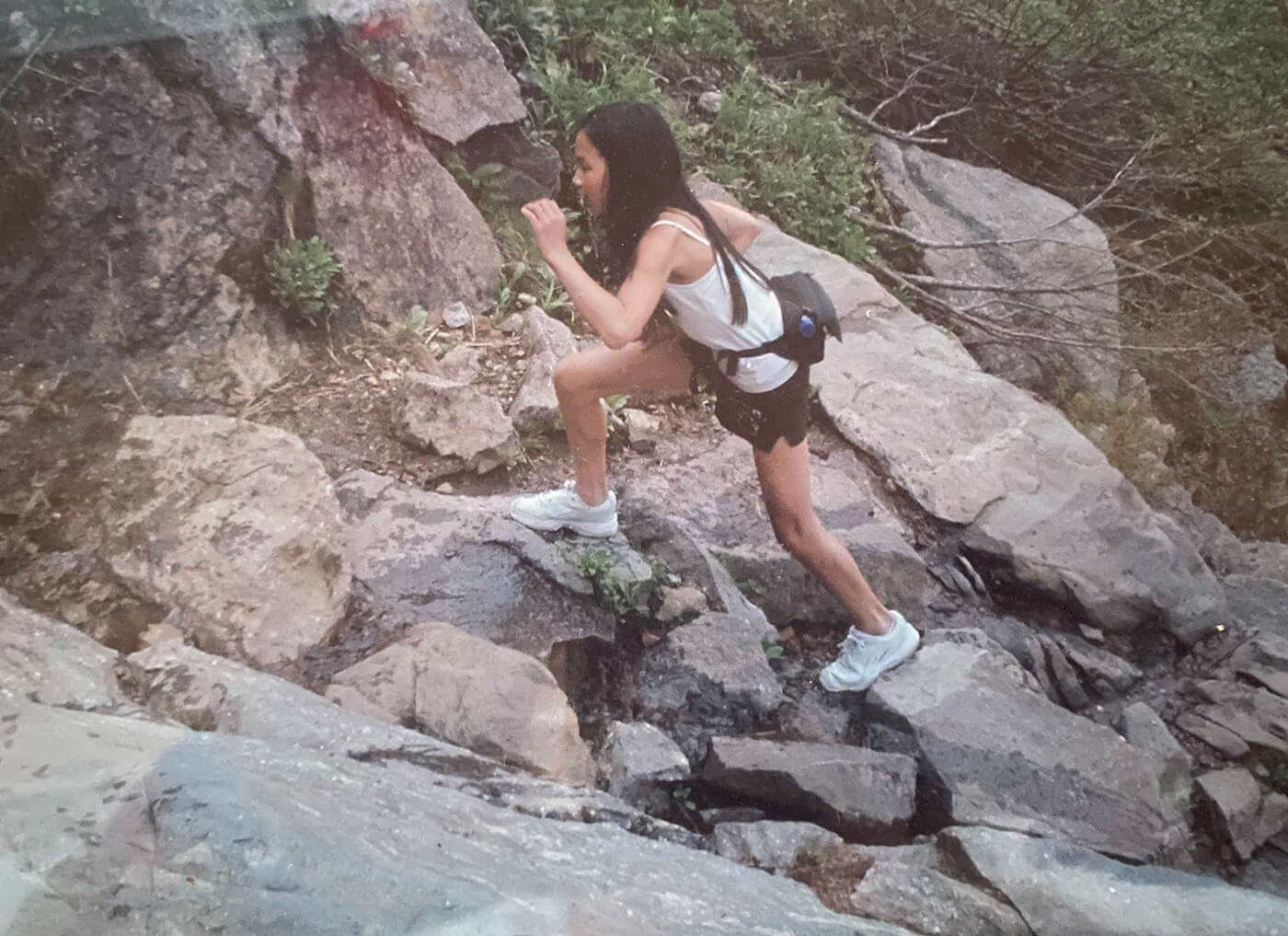

Jian power hikes a particularly steep section of mountain a few years after the Cannon Mountain adventure.

Nature has a way of guiding us through our human disharmonies if we can free ourselves to its influence. Hence, regular outdoor time is essential for the health of humans, our planet, and all life. Expanding one’s outdoor experiences to create opportunities to engage with people of diverse backgrounds seems to be a natural healing method that is both necessary and inevitable for AMC members—and all who love the outdoors—to take. “Including all as the goal,” which my son Cory epitomized in his short life, was my approach leading “Yeti” hikes each Saturday at the Blue Hills with AMC Southeastern Massachusetts Chapter prior to the pandemic. I am heartened by the steps AMC and its regional chapters are taking to better reflect their communities and work toward greater access to outdoor spaces for all.

I have great gratitude for those who have blazed the trails before us, mentoring many of us back to our true nature through being in nature. AMC has been key for me, as I often joined in on day, weekend, and extended adventures and absorbed the exploring spirit of my elders. I sense we are acknowledging that we still have a long way to go until all feel included on American waters and lands. This is a vital first step in letting go of often unspoken exclusions and moving toward inclusion. Nature is calling all and will welcome us if we will be well with her. Now if only human nature would follow.